Forward price

The forward price (or sometimes forward rate) is the agreed upon price of an asset in a forward contract. Using the rational pricing assumption, for a forward contract on an underlying asset that is tradeable, we can express the forward price in terms of the spot price and any dividends etc. For forwards on non-tradeables, pricing the forward may be a complex task.

Contents |

Forward Price Formula

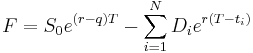

If the underlying asset is tradeable, the forward price is given by:

where

- F is the forward price to be paid at time T

- ex is the exponential function (used for calculating compounding interests)

- r is the risk-free interest rate

- q is the cost-of-carry

is the spot price of the asset (i.e. what it would sell for at time 0)

is the spot price of the asset (i.e. what it would sell for at time 0) is a dividend which is guaranteed to be paid at time

is a dividend which is guaranteed to be paid at time  where

where

Proof of the forward price formula

The two questions here are what price the short position (the seller of the asset) should offer to maximize his gain, and what price the long position (the buyer of the asset) should accept to maximize his gain?

At the very least we know that both do not want to lose any money in the deal.

The short position knows as much as the long position knows: the short/long positions are both aware of any schemes that they could partake on to gain a profit given some forward price.

So of course they will have to settle on a fair price or else the transaction cannot occur.

An economic articulation would be:

(fair price + future value of asset's dividends) - spot price of asset = cost of capital

Forward price = Spot Price - cost of carry

The future value of that asset's dividends (this could also be coupons from bonds, monthly rent from a house, fruit from a crop, etc.) is calculated using the risk-free force of interest. This is because we are in a risk-free situation (the whole point of the forward contract is to get rid of risk or to at least reduce it) so why would the owner of the asset take any chances? He would reinvest at the risk-free rate (i.e. U.S. T-bills which are considered risk-free). The spot price of the asset is simply the market value at the instant in time when the forward contract is entered into. So OUT - IN = NET GAIN and his net gain can only come from the opportunity cost of keeping the asset for that time period (he could have sold it and invested the money at the risk-free rate).

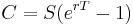

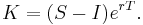

let:

- K = fair price

- C = cost of capital

- S = spot price of asset

- F = future value of asset's dividend

- I = present value of F (discounted using r )

- r = risk-free interest rate compounded continuously

- T = length of time from when the contract was entered into

Solving for fair price and substituting mathematics we get:

where:

(since  where j is the effective rate of interest per time period of T )

where j is the effective rate of interest per time period of T )

where ci is the i th dividend paid at time t i.

Doing some reduction we end up with:

Notice that implicit in the above derivation is the assumption that the underlying can be traded. This assumption does not hold for certain kinds of forwards.

Forward versus Futures prices

There is a difference between forward and futures prices when interest rates are stochastic. This difference disappears when interest rates are deterministic.

In the language of stochastic processes, the forward price is a martingale under the forward measure, whereas the futures price is a martingale under the risk-neutral measure. The forward measure and the risk neutral measure are the same when interest rates are deterministic.

See Musiela and Rutkowski's book on Martingale Methods in Financial Markets for a continuous time proof of this result. See van der Hoek and Elliott's book on Binomial Models in Finance for the discrete time version of this result.

See also

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||